Through the eyes of the Moon Witch

Marlon James' "African Game of Thrones" finally gets its middle

“Call me Ishmael.”

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…”

“In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.”

Every story needs a beginning, but not all beginnings are created equal. Most do little more than serve as an initial stepping stone to deliver the reader from the first page to the last. But others, like the ones above, are so potent and durable they enter a category all their own, rubbing elbows with your dad’s favorite movie quotes and other recitations we all know by heart even if we don’t quite remember where we learned them.

But if I had power over the cultural zeitgeist — and I have been told repeatedly that I do not — I would personally add one more opener to that list:

“The child is dead. There is nothing left to know.”

Those are the ten words that open Marlon James’ dark epic Black Leopard, Red Wolf, a 2019 National Book Award finalist and, much less prestigiously, one of my favorite fantasy novels of all time. That powerhouse opener not only perfectly sets up the story’s central conflict and introduces readers to James’ polyphonic writing style, but it also teases the novel’s central conceit: a narrator so unreliable that readers question his every word, yet so charismatic that they keep reading anyway. Why else power through 620 pages when the journey is revealed to be hopeless on page one?

But every story needs a middle, too, and so does every trilogy. While Black Leopard introduced readers to Marlon James’ Dark Star Trilogy about a mismatched fellowship journeying across a mythical African landscape in search of a lost boy, its sequel Moon Witch, Spider King, which hit bookshelves today, aims to tell the same story from a different point-of-view.

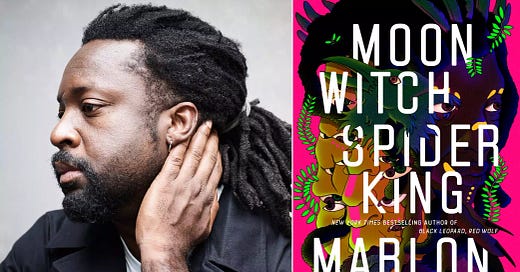

Left: Marlon James / Right: Moon Witch, Spider King (2022), Penguin Random House

James’ readers are probably starting to notice the outsized role perspective plays in this saga. Black Leopard was tightly narrated by Tracker, a hunter known for his nose, who is joined in adventure by a hodgepodge group of fighters, witches, and giants. They include the hyper-sexual shapeshifter known as the Leopard, his bowman and on-again-off-again fuck-buddy Fumeli, an alluring chieftain named Mossi, and Sadogo, a sad Ogo, one of the many strange creatures that populate James’ fantastical African landscape. What follows are their trials, trysts, revelations, and betrayals as seen through the myopic scope of Tracker’s wolf-like eyes.

But Marlon James doesn’t just tell the story from Tracker’s point of view, he literally hands the reins over to him. What results is a novel told almost entirely in flashback in the form of an interrogation between Tracker and a group of unknown captors, complete with Tracker’s exaggerations, rhetorical flourishes, and even outright lies. The book’s opening scene wastes no time establishing both this central storytelling device and James’ deft descriptive abilities and savage imagery:

Not everything the eye sees should be spoken by the mouth.

This cell is larger than the one before. I smell the dried blood of executed men; I hear their ghosts still screaming. Your bread carries weevils, and your water carries the piss of ten and two guards and the goat they fuck for sport. Shall I give you a story?

And boy does he.

Black Leopard, Red Wolf (2019), Penguin Random House

Several critics have called Black Leopard the African Game of Thrones, and not without reason: the violence is so brutal and sex so graphic that bodily fluids practically drip from the pages. But I would caution any hardcore Thrones fans from jumping in and expecting a Thrones retread. Black Leopard is much, much, much crazier than anything in A Song of Ice and Fire.

It’s also more tender. Black Leopard’s ragtag band of adventurers bound together by a common goal is my personal favorite fellowship since Tolkien’s. The central players have amazing chemistry. They banter. They quarrel. They laugh. They fight. And they fuck. A lot. But the sex rarely felt gratuitous to me, serving instead to flesh out key characters’ underlying motivation and attachments. The grace and nonchalance with which James handles extremely graphic sex — specifically gay sex, which many writers either glaze over or write with clinical detachment — was a wonder. The novel’s central love triangle in particular is a ravishing queer romance of exciting unconventionality that helped propel me through some of the novel’s most difficult sections.

It is under these seriously high expectations that Moon Witch, Spider King emerges onto the scene to bring readers back into the Dark Star Trilogy after three long years away. The follow-up to Black Leopard will continue the first part’s central conceit of handing the tale over to one of its central characters, while going one layer further: instead of continuing the tale, in typical sequel fashion, it will tell the same story as Black Leopard from a new pair of eyes, Rashomon-style. In this case, our new narrator is Sogolon, the eponymous Moon Witch, and another member of Tracker’s fellowship who plays a climactic role in the first novel’s cliffhanger ending. But Sogolon’s story is poised to go places Tracker’s could not because this Moon Witch has 177 years worth of secrets for Marlon James to dole out across 656 pages.

The sparse details released about the book’s plot leave readers with many open questions: how much will we learn about Sogolon’s life prior to her adventures with Tracker and company? Will we find out what motivated her fateful actions in Black Leopard? And, most pressing, will the sequel resolve the heartbreaking cliffhanger at the end of Black Leopard? Or will Moon Witch present us with a perspective equally as siloed as part one, intent on giving the story completely over to a new voice, thinking nothing of abandoning its inaugural protagonist?

Your guess is as good as mine. What I do know is that I haven't been this excited for a fantasy novel, or a sequel, in quite some time. Moon Witch, Spider King is firmly at the top of my to-read list.